Astronomers for Planet Earth

ooo

We are in the middle of a race and we are not doing so well. Wildfires, record heat waves, melting of the ice caps, more and more violent storms—the global warming is playing with the Earth’s intricate order, pushing it out of balance. Climate scientists have been warning us for decades about the problem, urging the governments to make plans to reduce carbon emissions. But it feels as if global warming is always one step ahead of us.

The goal of the famous Paris Agreement from 2016, signed by 189 members of the UNFCCC1United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, was to limit the increase in the global average temperature to 2 degrees Centigrade—apparently, we’re not doing so well. Under the pressure of the industry, while the next elections are always hanging over their heads, governments are reluctant to take a strong initiative without the support and understanding of the majority of the citizens. And the more we wait, the harder it will be to implement the changes without using unpopular draconian measures.

How to make the necessary transition into a carbon-free society? First, we need to change people’s mentality. While most of us acknowledge the problem, we are still reluctant to change our way of life. We need an incentive. It has to come from those who have means—we can’t expect the poor, those who struggle from day to day, to worry about the distant future. A group of astronomers2This is a post about astronomers. That doesn’t mean that other academic disciplines don’t have their own initiatives, not to mention countless organizations all around the world. I am not as much trying to praise Astronomers for planet Earth as to provide an example of good practice. decided to address the climate crisis with an initiative called Astronomers for Planet Earth.

The project unites astronomy students, educators, and scientists around the globe in order “to share their astronomical perspective about the Earth and climate change with the public.” While astronomers may not have a strong influence on world politics, they can provide the public with accurate information about the climate-related issues. For example, the pervasive argument that the rise in the global temperature is due to the solar activity can be debunked by data and communicated to the masses. As astronomers, we can also share our unique perspective on Earth—Earth as Pale blue dot is just one of the more famous examples. However, the initiative is not only about preaching and showing pretty pictures. Astronomers are also critically assessing the carbon emission of professional astronomy and searching for ways to reduce it.

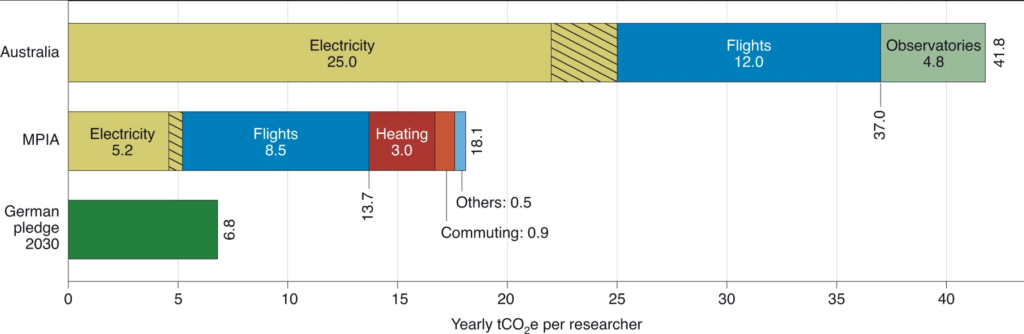

The work-related carbon emissions of an astronomer exceed that of an average adult for quite a lot. Jahnke et al. looked into the carbon emission produced by astronomers at MPIA (Heidelberg, Germany). They estimate about 18 tones CO2,eq work-related emissions per astronomer, compared to the 11 tones emitted by an average German citizen, and about three times the number that German pledged to reach by 2030. Astronomers thus produce about twice as much carbon emission as other citizens. There is little reason to assume that other institutes or observatories around the world fare much better. An important point is also that the average carbon emission of a person in less developed parts of the world is still much lower.

The big elephant in the room is flying. Astronomers fly a lot. They fly to conferences, group and board meetings, to observatories, or just to give a seminar at another institution. It comes as no surprise that flying accounts for most carbon emissions in an astronomer’s working life. However, even though we cannot completely abandon flying, and despite it being a rather touchy subject, there are options to reduce it.

For example, resident astronomers could perform most of the actual observations, significantly reducing the need for flying to and from the remote observatory sites. Flying may also be redundant for short meetings with a small number of attendants, like time or grant allocation committees.

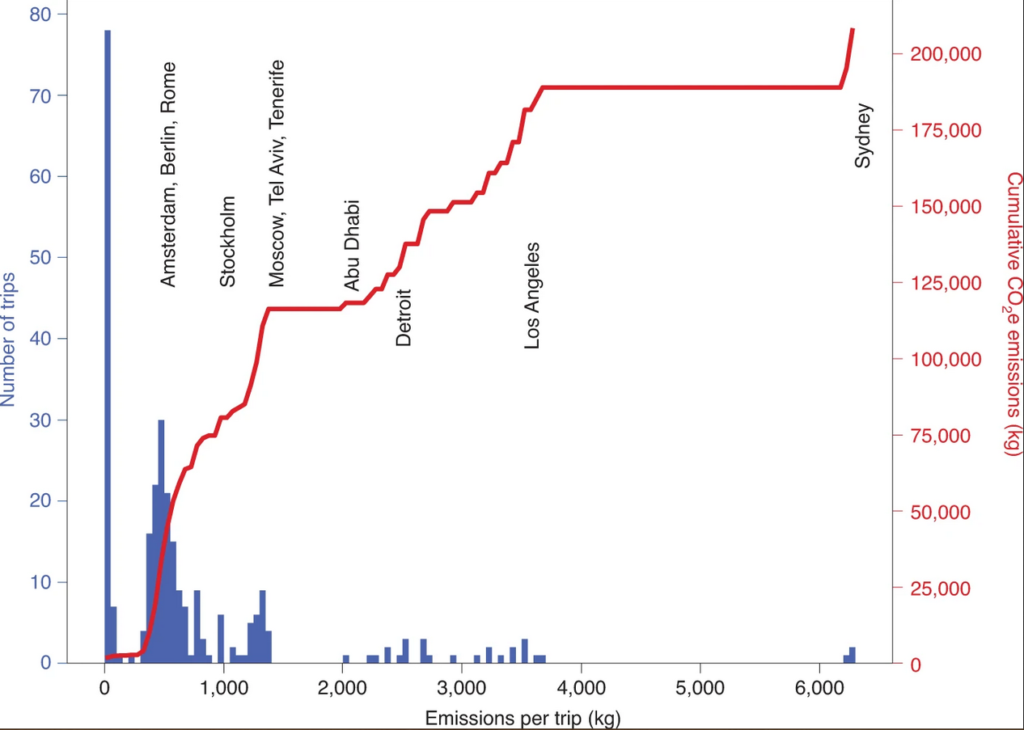

Conferences present a huge problem. Burtscher et al. compared the carbon footprint of two big European conferences: EWASS 2019 and EAS 2020. The former took place in Lyon, while this year’s meeting was entirely virtual due to COVID-19 measures. The study shows that 90 % of the participants in Lyon produced 50 % of the carbon emissions. In other words, participants who took intercontinental flights produced by far the most emissions. The study also estimated the carbon imprint of this year’s online meeting. The carbon emissions of EAS 2020 were a thousand times lower than those of EWASS 2019. Limiting intercontinental flights would therefore help a lot towards reducing the emissions. Perhaps a solution would be to restrict the in-person conferences and meetings to participants who can arrive at the location by train, while other scientists could attend online. This article goes in depth on how the virtual conferences and meetings can reduce the emissions.

Human contact cannot be abolished entirely, and it shouldn’t be. Brainstorming is much more effective in person than over zoom. Scientists meet colleagues, collaborators, and future employers at conferences. But something will have to change. At the moment, nobody has a perfect solution about the best course of action. The bottom line is, the studies show that astronomers can reduce carbon emissions if they want to. I guess that a very similar situation applies to all fields in academia and beyond.

Who will take the first difficult step?

There is only one planet that is well-suited for human life, and we live on it. Lately, Mars has become a focal point of many space enthusiasts. They believe that a civilization confined to one planet faces inevitable extinction because a supervolcano or an asteroid impact is bound to happen eventually; only a permanent settlement on Mars, or another place in the Solar system, ensures humanity’s survival. While in theory such thinking has its merit, let’s not fool ourselves: it will take a long, long time before any human outpost outside Earth will be even remotely self-sustainable. The aspiration to become a spacefaring race is commendable and should be pursued, but that doesn’t absolve us from the responsibility towards our one and only home—Earth. If we work together, we can still stop the threat posed by the global warming.